[ad_1]

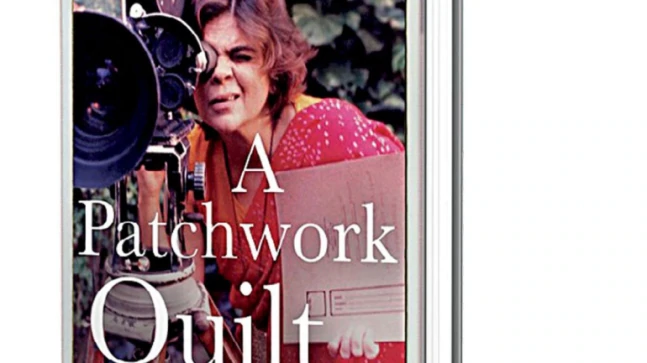

“I am skilled in plagiarising—from life,” Sai Paranjpye writes at one point in her candid, wide-ranging memoir A Patchwork Quilt: A Collage of My Creative Life. The immediate context is a millworker’s remark that Paranjpye incorporated into her screenplay for the 1990 film Disha, but reading this book, one realises that such skilful “plagiarism” applies to much of her output over a long, versatile career. It also requires the ability to absorb and store experiences and use them discerningly—a quality Paranjpye has shown in good measure, notwithstanding her admission that she doesn’t quite have a head for dates or chronology while remembering incidents.

During a phone interview, she elucidates by recalling a scene in her short film Angootha Chaap, about a village grandpa who learns to read and write. He is sitting in a bullock cart with his grandson, slate in hand, and stumbles when he sees the Devanagari symbol for ‘M’. Is this the ‘Bh’ sound, he wonders—and just at that moment, a goat nearby bleats ‘Maa’ and he gets it. “That’s how I have worked too,” Paranjpye says, “finding inspiration in what is around me.”

A Patchwork Quilt—her English translation of her bestselling Marathi memoir Saya: Maza Kalapravas—depicts a life that has been colourful and, importantly, multi-cultural from the beginning with many positive influences and experiences to draw on. She was brought up in Poona (now Pune), and for a few years, in Australia—by her unconventional, multi-faceted single mother Shakuntala Paranjpye and her maternal grandfather, or Appa, the mathematician R.P. Paranjpye; the book begins with a portrait of Shakuntala as writer, actress (she featured in V. Shantaram’s Duniya na Maane), social worker (who campaigned for family planning at a time when “birth control was never mentioned in polite society”) and later member of Parliament. “My mother was the biggest influence in my life and creativity, and my sense of humour is a reflection of hers,” Paranjpye says during our interview, though she also hints that Shakuntala’s domineering personality had another effect on her: “As a parent myself, I may have veered in the other direction as a result—being afraid of interfering with my own children.”

Still, the upshot was that she had a very well-rounded education, in Indian and Western culture: reading everything from Walter Scott to Jane Austen to Doctor Dolittle, while also learning Sanskrit verses by heart as a child—these recitations, she notes, aided her later in life when she learnt other languages such as French, or worked in radio and theatre.

“Who could have been lucky enough to have a mother or a grandfather like mine?” she says, “Appa came to terms with my being bad at math, and was very proud of whatever little creative things I did.” A collection of her fairy-tales was published when she was just eight. “I was roly-poly and unathletic as a child,” she tells me, “and other children didn’t want to include me in their games. I used my imagination to invent games, about stolen treasure and so on. My script-writing talent comes from a similar place.”

Readers who are familiar mainly with Paranjpye’s film work might well open this “quilt” in a rush to get to the later chapters about the conceptualisation and making of the breezy, perennially popular Chashme Buddoor and Katha, or the more serious-themed Saaz or Sparsh. And the book’s structure does allow for selective, dip-into-it-anywhere reading. There are many behind-the-scenes stories that fans of her movies will enjoy, such as a guerrilla shoot that had to be hurriedly executed at the Delhi Golf Club—for a gentle, romantic scene between Naseeruddin Shah and Shabana Azmi—because they couldn’t afford the charges for shooting there.

However, more patient readers will find that some of the most illuminating passages are the ones where she discusses her work in other fields: from radio to children’s theatre, from stints at the National School of Drama (NSD) and the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) to shooting teleplays, and even working on a campaign for the Tea Board of India in France, inventing tea cocktails on the spot for a guest who preferred his tea “strong”. Among her documentaries is one about painters of film hoardings and banners (one of whom poignantly tells her “Ours is real folk art. You don’t have to buy tickets to go to art galleries to see it”) and another about the pioneering music director Pankaj Mullick (“unfortunately, the film was not preserved or cared for, and not a single frame can be traced in the Doordarshan archives today”).

There are many insightful stories here about the special challenges of translating a play from one language (and culture) to another, or about Paranjpye’s approach to set design when mounting a production for children or adults. Such passages read like a necessary record of cultural documents that are always in danger of being unchronicled and forgotten. There are also recollections of seeking inspiration in sources as varied as Jean-Paul Sartre (with a play that offered a riposte to his observation, in No Exit, about hell being other people) and Neil Simon (a comedy about extramarital relationships that some viewers felt “betrayed” by), as well as accounts of steering her own stories across mediums. She writes with affection about the Maharashtrian folk-theatre form tamasha—avant-garde yet simple at the same time—and in one evocative passage, likens it to the French revue. “The same unshackled energy. The same joie de vivre. Two twins separated at birth and brought up under contrasting circumstances. I got to nurse both these twins. How lucky can one get?”

Elsewhere, there are amusing echoes between the personal experience and the creative one: early on, Paranjpye describes reading aloud as a child to her Appa while he shaved; decades later, in less propitious circumstances, she found herself reading out the Sparsh script to another man who was lathering his face (an initially indifferent Sanjeev Kumar, whom Paranjpye hoped to cast in the role of the blind school principal).

Having worked in so many capacities—writer, theatre and film director, actor, set designer—is there a particular role she finds most satisfying? Or a form she enjoys more than others? “I have dreams galore where I see myself in the midst of some mammoth extravaganza or activity,” she says, “and sometimes it is a film, sometimes TV, sometimes a particular form of theatre. I think of myself as a screenplay writer foremost, and I also enjoy editing—it’s stimulating to find the exact frame where one has to cut—but I’m not too good in other technical fields. Once I have selected a cameraman or music director who suits my purpose, I wouldn’t presume to give them detailed instructions on lighting or scoring.”

Given how much Paranjpye has done, across mediums, it is a bit humbling when she mentions the many things she didn’t get to do, the regrets, the projects left uncompleted. “We will need a whole day to recount everything I haven’t done.” But this may also be a side-effect of her restless, curious spirit; as she puts it, “I have a flighty temperament. When I’m doing tamasha, I yearn to change gears and do something like Shakespeare instead. When I’m working on something very serious, I feel like shifting to something simpler.”

“On the whole, though, I have always looked for the silver lining of humour in whatever I write or direct even in serious works like Disha, there is a quirky sense of fun somewhere. I strongly believe in entertainment, if it can be done in a wholesome way—and hang the message. “

Though she had often toyed with the idea of writing her reminiscences, this book might never have happened if she hadn’t been asked by the Marathi daily Loksatta to do a series of articles about her journey. “The damn thing got written only because I got that push,” she says. “I would have been lazy about it otherwise.” This last bit is the one part of our conversation that feels off—it’s hard to imagine Paranjpye, still working, still curious at 82, being lazy about anything.

[ad_2]

Source link