No escape? China’s crackdown on dissent goes global | CNN

Story highlights

China is taking its pursuit of critics outside its borders

Chinese dissidents in Thailand tell CNN they’re scared to go out

They say they fear being taken by Chinese security forces

Bangkok

CNN

—

Yu Yanhua hasn’t been back to her apartment in days.

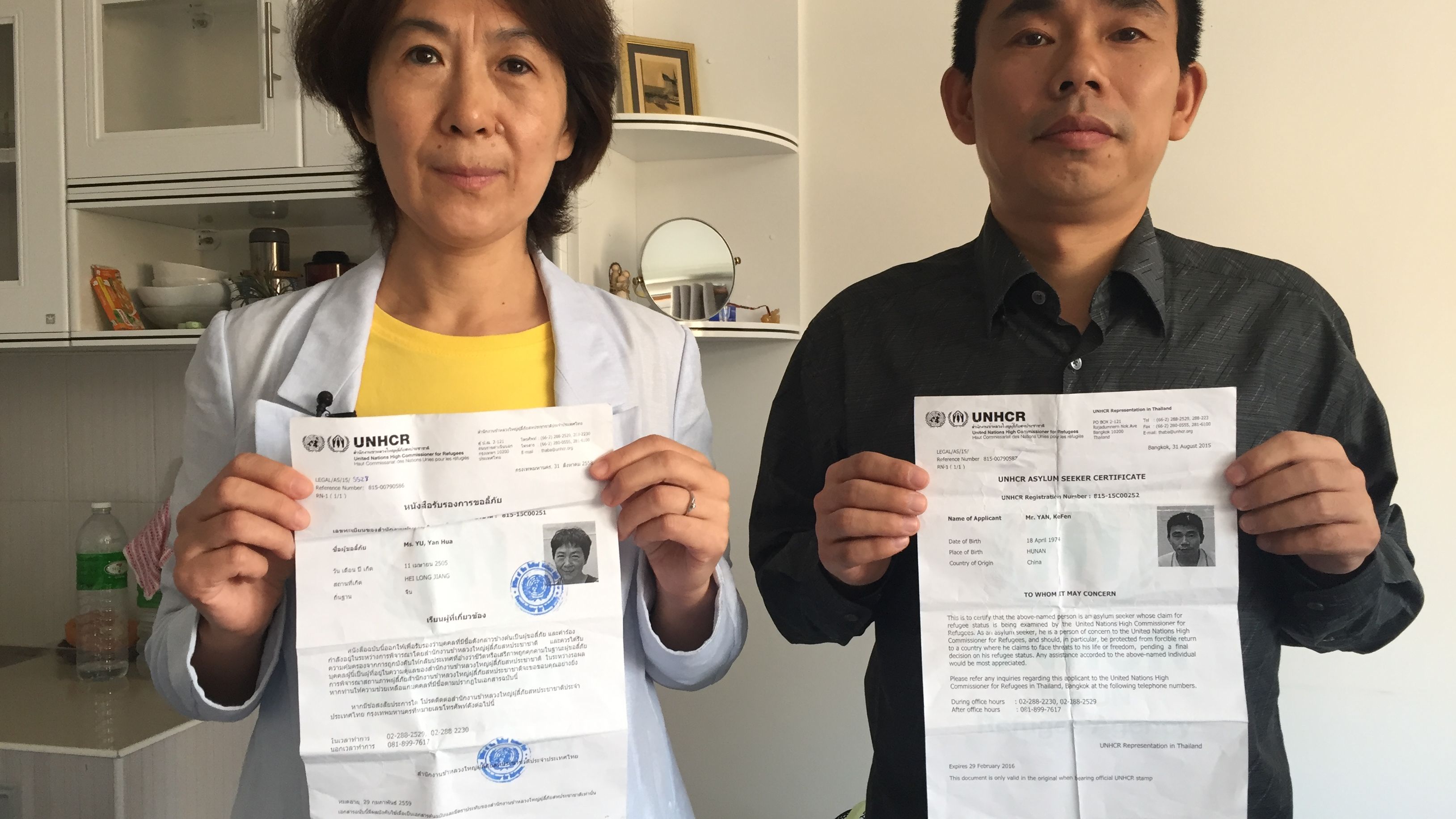

She’s been too frightened, she says, after at least four dissidents of Chinese origin were arrested or simply disappeared from Thailand in the last four months… only to resurface back in China in the custody of the government.

Yu is a pro-democracy activist who fled to Thailand last year to escape government repression in China.

“I thought I would get protection in Bangkok, that I wouldn’t have to live in fear of being arrested all the time,” she says, bursting into tears. Now she lives in fear of being snatched off the streets by Chinese agents.

READ: Three more missing Hong Kong booksellers turn up in China

For decades, critics of China’s ruling communist party have sought refuge in Thailand. But now it appears even foreign countries aren’t safe for political dissidents seeking to escape the long arm of the Chinese law.

A new pattern suggests Beijing is cracking down on critics beyond Chinese borders, not only in Thailand, but also in the autonomous former British colony of Hong Kong, where Chinese security services are not supposed to have legal jurisdiction.

Observers are most alarmed by the mysterious disappearance of a Swedish national of Chinese origin.

Gui Minhai is a part owner of a Hong Kong-based company that publishes gossipy books about China’s elite.

He was last seen in Thailand on October 17, driving out of the condominium complex where he owns an apartment in the resort of Pattaya. Thai police tell CNN they have no record of Gui leaving the country.

Three months later, Gui appeared weeping on state television in China. He claimed he returned to the country of his birth to turn himself in to police for breaking parole after a drunk driving accident thirteen years ago.

Thai and Swedish authorities don’t appear to be convinced.

A police official in Thailand, speaking to CNN on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the case, says Thai authorities are now working with Swedish officials to investigate Gui’s possible kidnapping.

Officials in Beijing continue to insist that Gui voluntarily handed himself over to Chinese authorities.

“He turned himself in to Chinese police,” foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang said on Tuesday.

“Trust that other governments will not break their own laws to cooperate with China,” he added.

Adding to the mystery is an unusual visit to Gui’s apartment on November 3 – long after he disappeared – by four unidentified men.

Gui’s maid Pisamai Phumulna told CNN they carried a letter in English, purportedly written by Gui, authorizing them to visit his room and take his computer.

She said the men appeared friendly. Only two of them spoke Thai, albeit with thick Chinese accents. Footage from the Silver Beach Condominium complex’s security camera captured the face and short-cropped hair of one of these mysterious visitors.

Was Gui Minhai’s TV confession made under duress? (2016)

At least four Hong Kong-based employees and business partners from Gui’s publishing company Mighty Current have also disappeared in recent months.

Critics accuse Chinese security services of abducting at least one of the book sellers in Hong Kong and dragging him back into mainland China.

News of British bookstore owner Lee Bo’s disappearance in January sparked street protests and a police investigation in Hong Kong.

The U.S. and Britain have both expressed concern about Gui, Lee, and three other missing book sellers.

Veteran China expert Mike Chinoy argues Beijing is sending a political message, especially when Chinese authorities parade former exiles on state television.

“This is really the first time that we’ve seen in such an over flagrant way – irrespective of the international fallout – that the Chinese government and security services have been going around and literally just taking people from other countries and spiriting them back to China,” says Chinoy, senior fellow at the USC U.S.-China Institute.

China’s international hunt for dissidents

Fear and paranoia

The disappearances and arrests have certainly struck fear into the heart of the small Chinese dissident exile community in Thailand.

Several pro-democracy activists who fled repression in China told CNN they no longer feel safe in the Thai capital.

“I avoid telling any Chinese person where I live,” says a dissident writer named Yi Feng. Every time he steps out onto the street, Yi says he’s on the look-out for anyone who appears to be Chinese.

They also fear arrest and extradition by the Thai authorities.

Last October, two members of a small exile Chinese opposition political party – Jiang Yefei and Dong Guangping – were arrested by Thai police.

Several weeks later, despite protests from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the two men were extradited to China and promptly thrown in prison.

Since the extradition of Dong, his wife, Gu Shuhua, and daughter fled Thailand for Canada. Speaking from Toronto, she says Dong’s capture has devastated her small family.

“The Chinese government put pressure on my husband for so long that he ran away [from China]. Why did they still need to chase us?” she asks, visibly shaking with grief and anger.

Gu’s husband was a police officer from a military family in Henan province. In the 1990s, he began publishing letters criticizing the Chinese government.

“Early on, he was aware of what the Chinese Communist Party’s dictatorship was doing to the country,” she says. “He worked in the security department, so he witnessed a lot of unjust events and policies that he did not agree with.”

In 2000, she says her husband was sentenced to three years in prison for his political activities.

After his release, he engaged in further protests against Beijing.

In some cases, Dong broke strict taboos by demonstrating to commemorate victims of the deadly 1989 crackdown in Tiananmen Square. Any mention of the deadly events of June 4, 1989 is strictly censored in China.

After yet another arrest in 2014, the couple finally decided to move with their daughter to Bangkok to escape mounting pressure from Chinese authorities.

“I thought Thailand would be better,” Gu says.

On October 28, 2015, Gu received a call saying her husband had been arrested along with Jiang by police in Bangkok. Dong was charged with entering the country without a passport.

Supporters launched a campaign to grant the men protected United Nations political refugee status.

Soon after, Gu says Dong received his U.N. refugee identification. On November 11th, she said Canada agreed to grant the family fast-track asylum. The couple enjoyed a happy visit the next day at the facility where Dong was incarcerated.

And then Jiang and Dong were both suddenly shipped back to China.

“When I heard from the U.N. that my husband was taken back to China, I lost my mind,” Gu says.

The UNHCR issued a statement on November 17, expressing deep concern about the two refugees who were supposed to be provided international protection.

The timing of the extradition was particularly alarming since it took place just days before the two men were scheduled to depart for North America.

“This action by Thailand is clearly a serious disappointment,” the UNHCR said.

Soon after, both Jiang and Dong appeared on Chinese state television being interrogated by Chinese police.

Fellow dissidents in Bangkok said Jiang had been instrumental in helping at least half a dozen political dissidents escape over the years from China to Thailand.

Gu has struggled with her daughter to attract attention to her husband’s case, staging small protests outside the Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

She says she has not been allowed to speak to her husband since he was taken to China in November.

“I hope he will take care of his health,” she says, sobbing. “I hope our family can reunite soon.”