This community’s quarter century without a newborn shows the scale of Japan’s population crisis | CNN

Tokyo

CNN

—

When Kentaro Yokobori was born almost seven years ago, he was the first newborn in the Sogio district of Kawakami village in 25 years. His birth was like a miracle for many villagers.

Well-wishers visited his parents Miho and Hirohito for more than a week – nearly all of them senior citizens, including some who could barely walk.

“The elderly people were very happy to see [Kentaro], and an elderly lady who had difficulty climbing the stairs, with her cane, came to me to hold my baby in her arms. All the elderly people took turns holding my baby,” Miho recalled.

During that quarter century without a newborn, the village population shrank by more than half to just 1,150 – down from 6,000 as recently as 40 years ago – as younger residents left and older residents died. Many homes were abandoned, some overrun by wildlife.

Kawakami is just one of the countless small rural towns and villages that have been forgotten and neglected as younger Japanese head for the cities. More than 90% of Japanese now live in urban areas like Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto – all linked by Japan’s always-on-time Shinkansen bullet trains.

That has left rural areas and industries like agriculture, forestry, and farming facing a critical labor shortage that will likely get worse in the coming years as the workforce ages. By 2022, the number of people working in agriculture and forestry had declined to 1.9 million from 2.25 million 10 years earlier.

Yet the demise of Kawakami is emblematic of a problem that goes far beyond the Japanese countryside.

The problem for Japan is: people in the cities aren’t having babies either.

“Time is running out to procreate,” Prime Minister Fumio Kishida told a recent press conference, a slogan that seems so far to have fallen short of inspiring the city dwelling majority of the Japanese public.

Amid a flood of disconcerting demographic data, he warned earlier this year the country was “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions.”

The country saw 799,728 births in 2022, the lowest number on record and barely more than half the 1.5 million births it registered in 1982. Its fertility rate – the average number of children born to women during their reproductive years – has fallen to 1.3 – far below the 2.1 required to maintain a stable population. Deaths have outpaced births for more than a decade.

And in the absence of meaningful immigration – foreigners accounted for just 2.2% of the population in 2021, according to the Japanese government, compared to 13.6% in the United States – some fear the country is hurtling toward the point of no return, when the number of women of child-bearing age hits a critical low from which there is no way to reverse the trend of population decline.

All this has left the leaders of the world’s third-largest economy facing the unenviable task of trying to fund pensions and health care for a ballooning elderly population even as the workforce shrinks.

Up against them are the busy urban lifestyles and long working hours that leave little time for Japanese to start families and the rising costs of living that mean having a baby is simply too expensive for many young people. Then there are the cultural taboos that surround talking about fertility and patriarchal norms that work against mothers returning to work.

Doctor Yuka Okada, the director of Grace Sugiyama Clinic in Tokyo, said cultural barriers meant talking about a woman’s fertility was often off limits.

“(People see the topic as) a little bit embarrassing. Think about your body and think about (what happens) after fertility. It is very important. So, it’s not embarrassing.”

Okada is one of the rare working mothers in Japan who has a highly successful career after childbirth. Many of Japan’s highly educated women are relegated to part-time or retail roles – if they reenter the workforce at all. In 2021, 39% of women workers were in part-time employment, compared to 15% of men, according to the OECD.

Tokyo is hoping to address some of these problems, so that working women today will become working mothers tomorrow. The metropolitan government is starting to subsidize egg freezing, so that women have a better chance of a successful pregnancy if they decide to have a baby later in life.

New parents in Japan already get a “baby bonus” of thousands of dollars to cover medical costs. For singles? A state sponsored dating service powered by Artificial Intelligence.

Whether such measures can turn the tide, in urban or rural areas, remains to be seen. But back in the countryside, Kawakami village offers a precautionary tale of what can happen if demographic declines are not reversed.

Along with its falling population, many of its traditional crafts and ways of life are at risk of dying out.

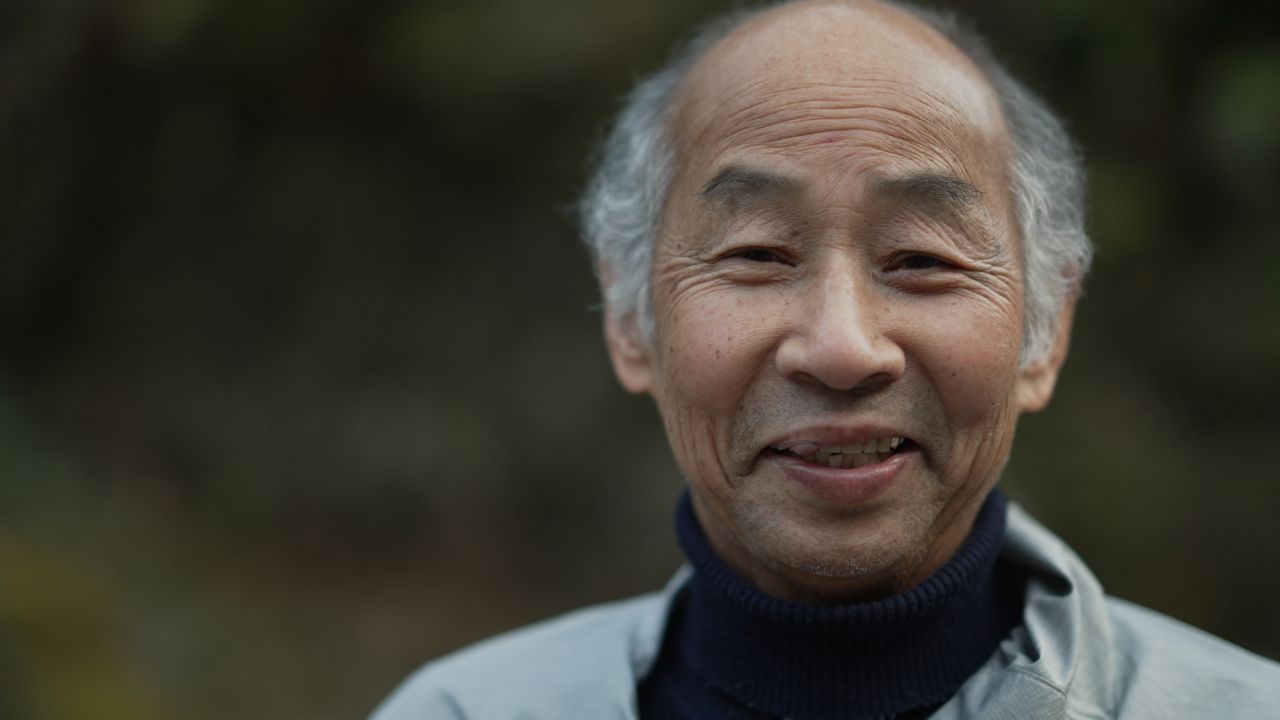

Among the villagers who took turns holding the young Kentaro was Kaoru Harumashi, a lifelong resident of Kawakami village in his 70s. The master woodworker has formed a close bond with the boy, teaching him how to carve the local cedar from surrounding forests.

“He calls me grandpa, but if a real grandpa lived here, he wouldn’t call me grandpa,” he said. “My grandson lives in Kyoto and I don’t get to see him often. I probably feel a stronger affection for Kentaro, whom I see more often, even though we are not related by blood.”

Both of Harumashi’s sons moved away from the village years ago, like many other young rural residents do in Japan.

“If the children don’t choose to continue living in the village, they will go to the city,” he said.

When the Yokoboris moved to Kawakami village about a decade ago, they had no idea most residents were well past retirement age. Over the years, they’ve watched older friends pass away and longtime community traditions fall by the wayside.

“There are not enough people to maintain villages, communities, festivals, and other ward organizations, and it is becoming impossible to do so,” Miho said.

“The more I get to know people, I mean elderly people, the more I feel sadness that I have to say goodbye to them. Life is actually going on with or without the village,” she said. “At the same time, it is very sad to see the surrounding, local people dwindling away.”

If that sounds depressing, perhaps it’s because in recent years, Japan’s battle to boost the birthrate has given few reasons for optimism.

Still, a small ray of hope may just be discernible in the story of the Yokoboris. Kentaro’s birth was unusual not only because the village had waited so long, but because his parents had moved to the countryside from the city – bucking the decades old trend in which the young increasingly plump for the 24/7 convenience of Japanese city life.

Some recent surveys suggest more young people like them are considering the appeals of country life, lured by the low cost of living, clean air, and low stress lifestyles that many see as vital to having families. One study of residents in the Tokyo area found 34% of respondents expressed an interest in moving to a rural area, up from 25.1% in 2019. Among those in their 20s, as many as 44.9% expressed an interest.

The Yokoboris say starting a family would have been far more difficult – financially and personally – if they still lived in the city.

Their decision to move was triggered by a Japanese national tragedy twelve years ago. On March 11, 2011, an earthquake shook the ground violently for several minutes across much of the country, triggering tsunami waves taller than a 10-story building that devastated huge swaths of the east coast and caused a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

Miho was an office worker in Tokyo at the time. She remembers feeling helpless as daily life in Japan’s largest city fell apart.

“Everyone was panicking, so it was like a war, although I have never experienced a war. It was like having money but not being able to buy water. All the transportation was closed, so you couldn’t use it. I felt very weak,” she recalled.

The tragedy was a moment of awakening for Miho and Hirohito, who was working as a graphic designer at the time.

“The things I had been relying on suddenly felt unreliable, and I felt that I was actually living in a very unstable place. I felt that I had to secure such a place by myself,” he said.

The couple found that place in one of Japan’s most remote areas, Nara prefecture. It is a land of majestic mountains and tiny townships, tucked away along winding roads beneath towering cedar trees taller than most of the buildings.

They quit their jobs in the city and moved to a simple mountain house, where they run a small bed and breakfast. He learned the art of woodworking and specializes in producing cedar barrels for Japanese sake breweries. She is a full-time homemaker. They raise chickens, grow vegetables, chop wood, and care for Kentaro, who’s about to enter the first grade.

The big question, for both Kawakami village and the rest of Japan: Is Kentaro’s birth a sign of better times to come – or a miracle birth in a dying way of life.