Uncontacted tribes and an Indian military base. Did a ‘spy’ balloon snoop on the Andaman and Nicobar islands? | CNN

CNN

—

When a strange white sphere appeared in the skies above the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in January 2022, it swiftly became a talking point in this sleepy Indian Ocean archipelago of 430,000 people.

Hundreds of members of the public spotted the strange object, which looked a little like a full moon, and were eager to speculate on what it was, reported local media. But “high-altitude surveillance balloon” didn’t seem high on many people’s guess list.

Many suggested it was a weather balloon; others, including local news outlet the Andaman Sheekha, thought that made no sense, ruling out the possibility on the grounds of the object’s shape, height, and photographs showing what appeared to be “eight dark panels” hanging from it.

Some did suggest spying might be involved, but that too seemed a strange explanation.

Under the headline, “Unidentified Flying Object over Port Blair city triggers curiosity and rumor,” the Sheekha posed a question: “In this age of ultra advanced satellites, who will use a flying object to spy?”

That question, experts say, has taken on a greater resonance this month, after the United States shot down a suspected Chinese surveillance balloon that spent days over American territory, including apparently lingering over nuclear missile silos in Montana.

US intelligence officials say the balloon – which China insists was a civilian weather research vessel – was part of an extensive Chinese surveillance program run from the island province of Hainan that has flown balloons over at least five continents in recent years.

Other governments have also raised concerns. Soon after the balloon was spotted over the US, Taiwan’s Foreign Ministry said the incident “should not be tolerated by the civilized international community,” adding it had experienced Chinese balloons flying over its territory in September 2021 and again in February 2022.

Japan meanwhile said it “strongly presumed” that three “balloon-shaped flying objects” detected in its airspace between November 2019 and September 2021 were “unmanned reconnaissance” aircraft flown by China.

But India – which administers the Andaman and Nicobar Islands – has remained conspicuously silent, despite questions being raised by the Indian media.

“Mystery balloon hovered over Andaman and Nicobar Islands around tri-service military drill,” reported India Today; “Chinese spy balloons, UFOs trigger paranoia among countries. Should India be worried?” asked Live Mint. “Reports Suggest India Was Targeted by Chinese Balloon Too,” ran a headline in The Wire; “Did a Chinese ‘spy’ balloon snoop on India too?” asked Firstpost.

China, meanwhile, has strongly denied running a balloon surveillance program. It maintains the vessel downed by the US was a weather balloon thrown off course and has also rejected Tokyo’s claims. Beijing said it firmly opposed “the Japanese side’s smear campaign against China” and said Japan should “stop following the US” by engaging in “deliberate speculation.”

“China is a responsible country that strictly abides by international law and respects the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries. (We) hope that all parties will look at it objectively,” China’s Foreign Ministry said in response to a question from CNN about whether the country had ever used balloons to spy on India.

But to many onlookers, the silence from New Delhi on the matter has been as baffling as the balloon-like object was to the readers of the Andaman Sheekha.

“I think (the Indian) government is being silent about it for the simple fact that (it) was unable to do anything about it,” said Sushant Singh, a senior fellow at New Delhi-based think tank Center for Policy Research.

“If it were to say that a spy balloon was found over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which is seen as a great bastion of Indian sovereignty, it would show the government in a very poor light.”

India will come under the international spotlight this year as it hosts two high-level summits – the G20 and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – and it is “desperately keen” for them to go well, Singh said.

And with a general election on the horizon in 2024, its leader Narendra Modi will be eager to look tough in the eyes of voters who swept him into power on a ticket of nationalism and a promise of India’s future greatness.

Acknowledging that a UFO – which may or may not have been spying – had floated above an archipelago that hosts a significant Indian military presence would compromise that message.

“Raising this issue of the balloon,” simply wouldn’t be in New Delhi’s interest, Singh concluded. “As a nationalist government, it would completely destroy and demolish its image within the country.”

But Manoj Kewalramani, a fellow of China studies at the Takshashila Institution in India, said silence was simply more New Delhi’s style.

“Historically, India has never spoken about these issues,” he said. “If the US has briefed India on the Chinese spying program, India will very careful about what they reveal, so as to not tarnish that relationship.”

CNN reached out to the Indian government for comment on this article but did not receive a response.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands may seem an unlikely target for international espionage.

The remote, sleepy archipelago at the junction of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea lies about 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of Aceh, Indonesia, and more than 1,800 miles (2,900 kilometers) from the Indian capital New Delhi. Only a few dozen of its more than 500 islands are even inhabited.

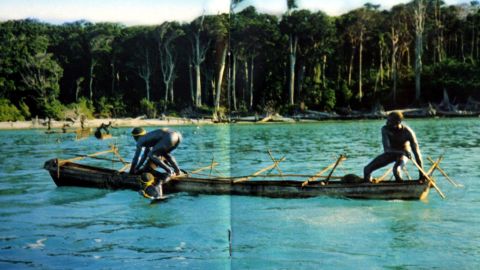

There is little commerce to speak of beyond fishing villages, and while the sandy beaches and rich biodiversity have made some of the islands popular with tourists, others are so remote they are home to uncontacted tribes.

In 2018, an American missionary, John Allen Chau, is thought to have been killed by the Sentinelese tribe after he arrived on North Sentinel Island, hoping to convert them to Christianity. In 2006, members of the same tribe killed two fishermen poachers whose boat drifted ashore. Two years earlier, one of its members was photographed firing arrows at a helicopter sent to check on their welfare following the Asian tsunami. Protection groups have urged the public to respect their wish to remain uncontacted.

But as obscure and remote as these islands may be, there are reasons they might be of interest to foreign intelligence agencies.

As a major outpost in the Indian Ocean, the islands join the Bay of Bengal with the wider Indo-Pacific, via the Malacca Strait – one of the busiest and most important trade routes in the world.

The location also makes the islands a strategic military asset for India, and they are home to the only integrated tri-service (army, navy, air force) base of the Indian armed forces.

In recent years, New Delhi has poured great effort into enhancing the islands’ prospects as a military base, with Modi in 2019 unveiling a decade-long plan to add more troops, warships and aircraft to its existing fleet.

“The islands are used for military deployment and dominate the area,” said Singh, from the Center for Policy Research. “Various Indian military leaders have described the islands as an ‘unsinkable carrier.’”

In the event of a military clash between China and the US over Taiwan, Singh said, “the US could ask India for support from the islands.”

“India has also been very protective about the islands. Very rarely have they allowed foreign military to exercise on land on these islands,” he added.

Kewalramani, from the Takshashila Institution, said China “would want to know what’s happening on the (Andaman and Nicobar) islands.”

However, he also said it remained unclear “whether they would do that through a balloon and whether a balloon could gather enough intel.”

To many commentators, the whole saga is less about what may or may not have been a surveillance balloon, and more about the Modi government’s reticence to engage on issues involving China for fear of sparking a diplomatic crisis ahead of next year’s Indian election.

While there may be some sensitive military secrets to be gleaned from Andaman and Nicobar islands, analysts suggest the real reason for tight lips in New Delhi may be connected to what is happening thousands of miles to the north, along India’s 2,100-mile (3,380-kilometer) disputed border with China.

It’s here in the thin air and freezing temperatures of the Himalayas that troops from the two nuclear-armed neighbors have clashed over the past few years, in what are startling reminders of India and China’s combustible relationship.

Tensions along the de factor border have been simmering for more than 60 years and have spilled over into war before. In 1962 a month-long conflict ended in a Chinese victory and India losing thousands of square miles of territory.

But rarely in recent years have those tensions been as high as they are now. Since a clash involving hand-to-hand fighting in 2020 claimed the lives of at least 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers, both sides have deployed thousands of troops to the area, where they remain in what appears to be a semi-permanent stand-off.

Why do India and China spar at the border?

“The whole character of the border changed in 2020. China did something that they had not done before … they came into occupied areas … and refused to withdraw,” said former Lt. Gen. Rakesh Sharma, whose more than 40 years in the Indian army included a stint commanding the Fire and Fury Corps in the Ladakh area of the border.

There are now signs things may be heating up once again, according to Arzan Tarapore, South Asia research scholar at Stanford University’s Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center.

A brawl between troops from the two sides in December – what the Indian government characterized as a “physical scuffle” – was “part of the steady drumbeat of China building its military presence, asserting its control over disputed areas, and probing Indian defenses,” Tarapore said.

“It was just one episode in a string of episodes, and India should certainly expect more – and probably bigger – such probes and incursions in the future,” he added.

With the border issue heating up, analysts say Modi faces a difficult diplomatic balancing act.

On one hand, he needs to project a strong image to voters and show he is willing to stand his ground against China’s pressure at the border.

On the other, he must be careful to avoid inflaming the already tense relationship with Beijing by wading into China’s dispute with Washington over the balloon shot down off the US East Coast.

One reading of India’s silence may be that is adopting Theodore Roosevelt’s famous foreign policy maxim of, “Speak softly, and carry a big stick.”

New Delhi recently announced a 13% hike in its annual defense budget to 5.94 trillion rupees ($72.6 billion) – which is expected to fund, among other things, new access roads and fighter jets to be based along the disputed border.

But, as with the UFO in the Andaman and Nicobars, experts say New Delhi sometimes gives the impression that the less said about the border the better.

Kenneth Juster, a former US ambassador to India, told Indian television channel Times Now that New Delhi preferred Washington not to comment on Chinese aggression at the Himalayan border.

“The restraint in mentioning China in any US-India communication or any Quad communication comes from India, which is very concerned about not poking China in the eye,” he said, referring to discussions of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – a strategic US-led group that includes India, Japan and Australia and that Beijing is convinced is aimed at containing China’s rise.

Modi has largely avoided speaking publicly on the border issue, going as far as saying on live television shortly after the deadly 2020 clashes that, “No one has intruded and nor is anyone intruding.”

“He wants the crisis to go away. His reaction is to avoid talking about it,” said Singh, the analyst. “Propaganda and PR have led many Indians to believe that things (at the disputed border) are OK.”

Kewalramani, the China expert, said India simply preferred a lower-key approach in pushing back against Beijing, noting it had cracked down on Chinese businesses, including by banning some Chinese apps.

“While there aren’t huge gestures, it is part of India’s diplomatic culture to avoid aggression,” he said.

The problem with that approach, others warned, was that it risked making India appear weak.

“Considering that a crisis on the border is still ongoing, and continues to haunt India and China, the silence does not bode well for India,” Singh said.

“It emboldens China.”